This data scientist’s perspective rings true to me

Read on timdellinger.substack.com/p/hey-wait-is-employee-performance

Tony – From the Outside

This data scientist’s perspective rings true to me

Read on timdellinger.substack.com/p/hey-wait-is-employee-performance

Tony – From the Outside

I think it is human instinct to interpret why organisations and people make bad decisions through a moral lens (e.g. they are bad people) but I am more interested in the question why organisations run by ordinary people seem to end up with often substandard outcomes. My current interaction with one of my financial service providers comes to mind.

This post by Marc Rubinstein and Dan Davies offers some insights that have prompted me to order Dan’s new book

What do bad decision-making organizations have in common? Quite a few things, but one of the clearest signs is something you might call an “accountability sink”.

Tony – From the Outside

This is possibly a bit self indulgent but “From The Outside” is fast approaching the 5th anniversary of its first post so I thought it was time to look back on the ground covered and more importantly what resonated with the people who read what I write.

The blog as originally conceived was intended to explore some big picture questions such as the ways in which banks are different from other companies and the implications this has for thinking about questions like their cost of equity, optimal capital structure, risk appetite, risk culture and the need for prudential regulation. The particular expertise (bias? perspective?) I brought to these questions was that of a bank capital manager, with some experience in the Internal Capital Adequacy Assessment Process (ICAAP) applicable to a large Australian bank and a familiarity with a range of associated issues such as risk measurement (credit, market, operational, interest rate etc), risk appetite, risk culture, funds transfer pricing and economic capital allocation.

Over the close to 5 years that the blog has been operational, something in excess of 200 posts have been published. The readership is pretty limited (196 followers in total) but hopefully that makes you feel special and part of a real in crowd of true believers in the importance of understanding the questions posed above. Page views have continued to grow year on year to reach 9,278 for 2022 with 5,531individual visits.

The most popular post was one titled “Milton Friedman’s doctrine of the social responsibility of business” in which I attempted to summarise Friedman’s famous essay “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits” first published in September 1970. I was of course familiar with Friedman’s doctrine but only second hand via reading what other people said he said and what they thought about their framing of his argument. You can judge for yourself, but my post attempts to simply summarise his doctrine with a minimum of my own commentary. It did not get as much attention but I also did a post flagging what I thought was a reasonably balanced assessment of the pros and cons of Friedman’s argument written by Luigi Zingales.

The second most popular post was one titled “How banks differ from other companies“. This post built on an earlier one titled “Are banks a special kind of company …” which attempted to respond to some of the contra arguments made by Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig. Both posts were based around three distinctive features that I argued make banks different and perhaps “special” …

- The way in which net new lending by banks can create new bank deposits which in turn are treated as a form of money in the financial system (i.e. one of the unique things banks do is create a form of money);

- The reality that a large bank cannot be allowed to fail in the conventional way (i.e. bankruptcy followed by reorganisation or liquidation) that other companies and even countries can (and frequently do); and

- The extent to which bank losses seem to follow a power law distribution and what this means for measuring the expected loss of a bank across the credit cycle.

The third most popular post was titled “What does the “economic perspective” add to can ICAAP“ and this to be frank this was a surprise. I honestly thought no one would read it but what do I know. The post was written in response to a report the European Central Bank (ECB) put out in August 2020 on ICAAP practices it had observed amongst the banks it supervised. What I found surprising in the ECB report was what seemed to me to be an over reliance on what economic capital models could contribute to the ICAAP.

It was not the ECB’s expectation that economic capital should play a role that bothered me but more a seeming lack of awareness of the limitations of these models in providing the kinds of insights the ECB was expecting to see more of and a lack of focus on the broader topic of radical uncertainty and how an ICAAP should respond to a world populated by unknown unknowns. It was pleasing that a related post I did on John Kay and Mervyn King’s book “Radical Uncertainty : Decision Making for an Unknowable Future” also figured highly in reader interest.

Over the past year I have strayed from my area of expertise to explore what is happening in the crypto world. None of my posts have achieved wide readership but that is perfectly OK because I am not a crypto expert. I have been fascinated however by the claims that crypto can and will disrupt the traditional banking model. I have attempted to remain open to the possibility that I am missing something but remain sceptical about the more radical claims the crypto true believers assert. There are a lot of fellow sceptics that I read but if I was going to recommend one article that offers a good overview of the crypto story to date it would be the one by Matt Levine published in the 31 October 2022 edition of Bloomberg Businessweek.

I am hoping to return to my bank capital roots in 2023 to explore the latest instalment of what it means for an Australian bank to be “Unquestionably Strong” but I fear that crypto will continue to feature as well.

Thank you to all who find the blog of interest – as always let me know what I missing.

Tony – From the Outside

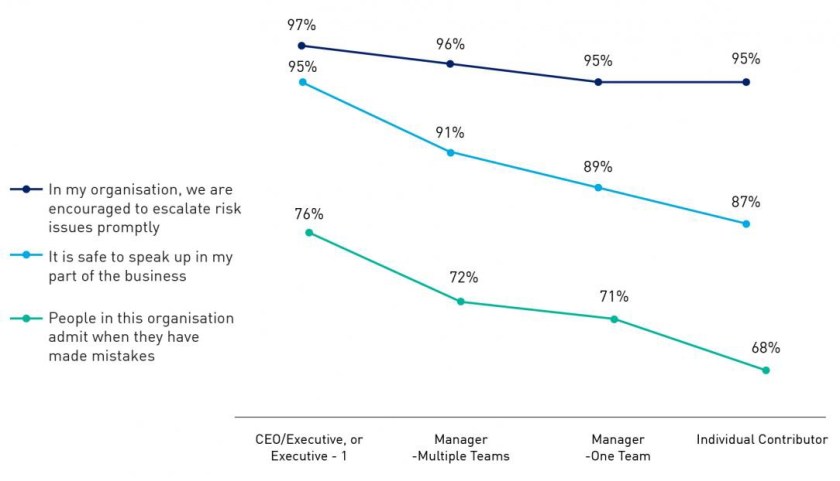

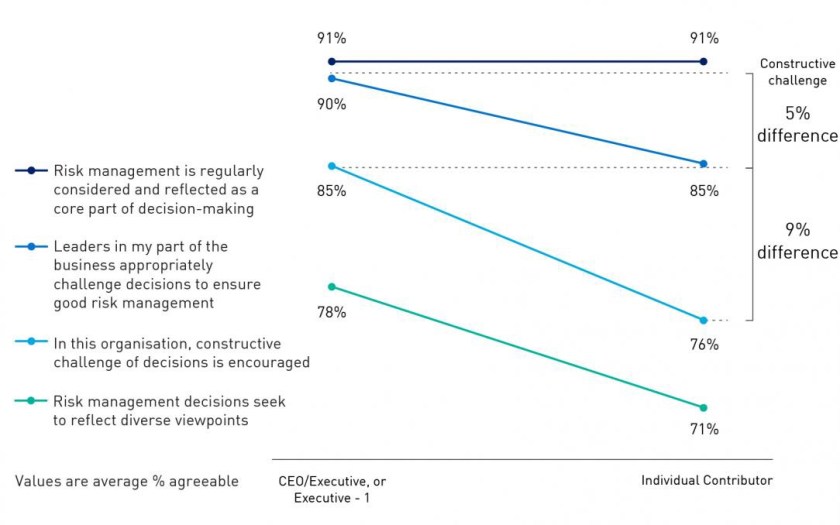

APRA today released the results of a survey of how Australian ADI’s (i.e. “banks” for anyone reading outside Australia) believe they are doing on the question of risk culture.

What I found most interesting was the gap between what the executives believe and what the people on the front line believe as reflected in these two charts

Creating an environment in which people truely feel safe to speak up is hard but it does appear that there is a lot more work to do. The first book that comes to mind when I read about risk culture is Creativity, Inc which explores (amongst other things) how Pixar institutionalised “Candour” into the business. Michael Mauboussin’s “The Success Equation” and Greg Ip’s “Foolproof” are also useful guides for avoiding hubris and general overconfidence in your risk management process.

I have to say that the challenge of speaking up is one that resonates with me from my time in the front line and it appears that there is still more to do. Personally I quite liked Pixar’s “brains trust” solution.

Tony – From the Outside

The story of people in finance doing dumb things never gets old for me. I will probably shut my blog down when I figure out why the same old mistakes keep getting repeated. I look forward to reading Duncan Mavin’s book but in the interim John Hempton’s review offers a quick recap.

— Read on brontecapital.blogspot.com/2022/10/an-old-story-in-modern-times-duncan.html

Tony – From the Outside

Joseph Campbell’s “The Hero with a Thousand Faces” is a great book. It offers insights into some deep ideas about how the world does (or should) work that have influenced a wide variety of people including George Lucas and Ray Dalio and was included in Time magazine’s list of the top 100 books.

Barry Ritholz did a short, but insightful, post here where he reminds us that the timeless appeal of the narrative that Campbell explores can also mislead us.

Our narrative bias for compelling stories can prevent us from seeing the forest for trees. Dramatic tales with clearly delineated Good & Evil are more memorable and emotionally resonant than dry data and tedious facts. Try as you might, finding a singular cause of some terrible economic outcome is an exercise in futility. Instead, you will find a long history of political, economic, psychological, and (occasionally) irrational drivers that eventually led to some disaster.

We look for the spark that ignites the room full of hydrogen, instead of 1,000 other factors that created the conditions precedent. You can find example after example of disasters widely thought of as “single event causes;” upon closer examination, they are revealed as the result of far more complex circumstances and countless interactions

https://ritholtz.com/2021/09/misunderstanding-narratives-the-heros-journey/

This for me is an insight that rings very true but is often forgotten to feed our appetite for reducing complex stories to simple morality plays. I like the stories as much as the next person but the downside is that the simple appealing story distracts us from understanding the route causes of why things like the GFC happened and leave us exposed to the risk that they just keep repeating in different forms.

Tony – From the Outside

This essay by Luigi Zingales (University of Chicago – Booth School of Business) offers a useful assessment of the rights and wrongs of Friedman’s shareholder responsibility doctrine.

Zingales argues that part of the problem with Friedman is that his argument is treated as a statement of doctrine to which one pledges allegiance as opposed to a theorem that can be used to analyse and understand what is happening in the real world.

Zingales therefore restates Friedman as a theorem for analysing the conditions under which it would be socially optimal for corporate executives to focus solely on maximising corporate profits. He refers to this as the “Friedman Separation Theorem” and argues that it holds if the following three conditions are met:

First, companies should operate in a competitive environment, which I will define as firms being both price and rules takers. Second, there should not be externalities (or the government should be able to address perfectly these externalities through regulation and taxation). Third, contracts are complete, in the sense that we can specify in a contract all relevant contingencies at no cost.

“Friedman’s Legacy: From Doctrine to Theorem” – Zingales – Pro Market 13 Oct 2020

Whether you agree or disagree with it, one of the great attractions of this doctrine/theorem is that it makes the life of a corporate executive much simpler. That gives the idea an obvious appeal.

Zingales notes that on a technical level, the Friedman Separation Theorem is a restatement of what economists refer to as the “First Welfare Theorem” (also known as the “Invisible Hand Theorem”) which holds that markets produce socially optimal outcomes under certain conditions.

Zingales argues that Friedman also recognised that he needed something catchier for his argument to impact public debate so he framed the argument around an appeal to the core American values of freedom, independence and the principle of “no taxation without representation” embedded in the story of the American Revolution.

Zingales works through each of the three assumptions he has identified as underpinning the Friedman Separation Theorem, highlighting the ways in which the are not valid descriptions of how the economy actually operates.

Zingales sums up his review by posing the question how should we interpret the practical implications of Friedman’s idea in 2020? His answer has two legs. Firstly he argues that we need to distinguish between small to medium size companies and their larger cousins which have power in various forms:

If you are a small to medium-sized company, .., a company with no market power and no real power to influence regulation or elections, maximizing shareholder welfare is the right goal to follow. Especially if this goal is pursued with attention not only to legal rules but also ethical customs, like Friedman advocated, but most companies ignored.

However, Zingales argues that we should also recognise the limitations of the Friedman Separation Theorem when we are dealing with corporate entities, and their executives, which have real power.

When it comes to super corporations, corporations that have market power, like Google and Facebook, or political power, like BlackRock or JP Morgan, or regulatory power, like DuPont or Monsanto, a single-minded pursuit of shareholder value maximization can be extremely bad for society.

This, Zingales argues, is the reason why he and Oliver Hart have advocated requiring boards of monopolies, like Google, or of firms too big to regulate, like Blackrock, to maximize social welfare, the utility of society as a whole, not shareholder welfare.

Zingales concludes that “Friedman was more right than his detractors claim and more wrong than his supporters would like us to believe”:

His “theorem” has greatly contributed to determining when maximizing shareholder value is good for society and when it is not. The discipline imposed by Friedman’s theorem also forces greater accountability on managers. In the world of 2020, the biggest shareholder in most corporations is all of us, who have their pension money invested in stocks. We are the real silent majority. Corporate managers finance political candidates, lobby for self-serving legislation, and capture regulation. They have the power to use our money to fight against our own interest. While Friedman did not anticipate these degenerations, he warned us against the risk of unaccountable managers. This warning will remain his most enduring contribution.

Irrespective of whether you agree or disagree with the proposed solution to the big company problem, Zingales essay is one of the better contributions to the Corporate Social Responsibility and Shareholder Value Maximisation debate that I have come across. It is a short read but worth it.

For anyone wanting to dig deeper, the collection of 27 essays that Zingales references in his essay can be found here.

Tony – From the Outside

I have been digging into the debate about what Milton Friedman got right and wrong about the social responsibility of business. I am still in the process of organising my thoughts but this discussion on the “Capitalisn’t” podcast is, I think, worth listening to for anyone interested in the questions that Friedman’s 1970 essay raises.

You can find the podcast here

podcasts.apple.com/au/podcast/what-is-the-alternative-to-friedmans-capitalism/id1326698855

Tony – From the Outside

I recently flagged a post by Aswath Damodaran on his “Musings on Markets” blog which offered a sceptical perspective on the claims being made in favour of ESG based investing.

The Knowledge at Wharton website has a summary of some research that offers another perspective on ESG and Socially Responsible investment approaches. The research is described as providing “… a theoretical framework for how ESG (environmental, social and governance) investing affects stock prices and corporate behavior.”

The research paper is behind a paywall but you can find the Knowledge at Wharton summary here – knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/esg-investors-happy-settle-lower-returns/

Tony – From the Outside

The 50th anniversary of Milton Friedman’s 1970 essay has triggered a deluge of commentary celebrating or critiquing the ideas it proposed. My bias probably swings to the “profit maximisation is not the entire answer” side of the debate but I recognised that I had not actually read the original essay. Time, I thought, to go back to the source and see what Friedman actually said.

I personally found this exercise useful because I realised that some of the commentary I had been reading was quoting him out of context or otherwise reading into his essay ideas that I am not sure he would have endorsed. I will leave my comment on the merits of his doctrine to another post.

Friedman’s famous (or infamous) conclusion is that in a “free” society…

“there is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception fraud.”

My more detailed notes on what Friedman wrote can be found here. That note includes lengthy extracts from the essay so that you can fact check my paraphrasing of what he said. My summary of his argument as I understand it runs as follows:

But the doctrine of “social responsibility” taken seriously would extend the scope of the political mechanism to every human activity. It does not differ in philosophy from the most explicitly collectivist doctrine. It differs only by professing to believe that collectivist ends can be attained without collectivist means.

That is why, in my book “Capitalism and Freedom,” I have called it a “fundamentally subversive doctrine” in a free society, and have said that in such a society, “there is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception fraud.”

Hopefully what I have set out above offers a fair and unbiased account of what Friedman actually said. If not then tell me what I missed. I think he makes a number of good points but, as stated at the beginning of this post, I am not comfortable with the conclusions that he draws. I am working on a follow up post where I will attempt to deconstruct the essay and set out my perspective on the questions he sought to address.

Tony – From the Outside