This is the question that Sir Paul Tucker poses in a BIS Working Paper titled “Is the financial system sufficiently resilient: a research programme and policy agenda” (BIS WP790) and answers in the negative. Tucker’s current role as Chair of the Systemic Risk Council and his experience as Deputy Governor at the Bank of England from 2009 to 2013 suggests that, whether you agree or disagree, it is worth reading what he has to say.

Tucker is quick to acknowledge that his assessment is “… intended to jolt the reader” and recognises that he risks “… overstating weaknesses given the huge improvements in the regulatory regime since 2007/08”. The paper sets out why Tucker believes the financial system is not as resilient as claimed, together with his proposed research and policy agenda for achieving a financial system that is sufficiently resilient.

Some of what he writes is familiar ground but three themes I found especially interesting were:

- The extent to which recourse by monetary policy to very low interest rates exposes the financial system to a cyclically higher level of systemic risk that should be factored into the resilience target;

- The need to formulate what Tucker refers to as a “Money Credit Constitution” ; and

- The idea of using “information insensitivity” for certain agreed “safe assets” as the target state of resilience for the system.

Financial stability is of course one of those topics that only true die hard bank capital tragics delve into. The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) demonstrated, however, that financial stability and the resilience of the banking system is also one of those topics that impacts every day life if the technocrats get it wrong. I have made some more detailed notes on the paper here for the technically inclined while this post will attempt (and likely fail) to make the issues raised accessible for those who don’t want to read BIS working papers.

Of the three themes listed above, “information insensitivity” is the one that I would call out in particular. It is admittedly a bit clunky as a catch phrase but I do believe it is worth investing the time to understand what it means and what it implies for how the financial system should be regulated and supervised. I have touched on the concept in a couple of previous posts (here, here, and here) and, as I worked through this post, I also found some interesting overlaps with the idea introduced by the Australian Financial System Inquiry that systemically important banks should be required to be “unquestionably strong”.

How resilient is the financial system?

Tucker’s assessment is that Basel III has made the financial system a lot safer than it was but less resilient than claimed. This is because the original calibration of the higher capital requirements under Basel III did not allow for the way in which any subsequent reduction in interest rates means that monetary policy has less scope to help mitigate economic downturns. All other things being equal, any future stress will have a larger impact on the financial system because monetary policy will have less capacity to stimulate the economy.

We could quibble over details:

- The extent to which the capital requirements have been increased by higher Risk Weights applied to exposures (Tucker is more concerned with the extent to which capital requirements get weakened over time in response to industry lobbying)

- Why is this not captured in stress testing?

- The way in which cyclical buffers could (and arguably should) be used to offset this inherent cyclical risk in the financial system.

But his bigger point sounds intuitively right, all other things being equal, low interest rates mean that central banks will have much less scope to stimulate the economy via monetary policy. It follows that the financial system is systemically riskier at this point in time than historical experience with economic downturns might suggest.

How should we respond (in principle)?

One response is common equity and lots of it. That is what is advocated by some academic commentators , influential former central bankers such as Adair Turner and Mervyn King, and most recently by the RBNZ (with respect to the quantum and the form of capital.

Tucker argues that the increased equity requirements agreed under Basel III are necessary, but not sufficient. His point here is broader than the need to allow for changes in monetary policy discussed above. His concern is what does it take to achieve the desired level of resilience in a financial system that has fractional reserve banking at its core.

”Maintaining a resilient system cannot sanely rely on crushing the probability of distress via prophylactic regulation and supervision: a strategy that confronts the Gods in its technocratic arrogance. Instead, low barriers to entry, credible resolution regimes and crisis-management tools must combine to ensure that the system can keep going through distress. That is different from arguing that equity requirements (E) can be relaxed if resolution plans become sufficiently credible. Rather, it amounts to saying that E would need to be much higher than now if resolution is not credible.”

“Is the Financial system sufficiently resilient: a research programme and policy agenda” BIS WP 790, p 23

That is Tucker’s personal view expressed in the conclusion to the paper but he also advocates that “unelected technicians need to frame the question [of target resilience] in a digestible way for politicians and public debate“. It is especially important that the non-technical people understand the extent to which there may be trade-offs in the choice of how resilient the financial system should be. Is there, for example, a trade-off between resilience and the dynamism of the financial system that drives its capacity to support innovation, competition and growth? Do the resource misallocations associated with credit and property price booms damage the long run growth of the economy? And so on …

Turner offers a first pass at how this problem might be presented to a non-technical audience:

Staying with crisp oversimplification, I think the problem can be put as follows:

• Economists and policymakers do not know much about this. Models and empirics are needed.

• Plausibly, as BIS research suggests, credit and property price booms lead resource misallocation booms? Does that damage long-run growth?

• Even if it does, might those effects be offset by net benefits from greater entrepreneurship during booms?

• Would tough resilience policies constrain capital markets in ways that impede the allocation of resources to risky projects and so growth?

If there is a long-run trade off, then where people are averse to boom-bust ‘cycles’, resilience will be higher and growth lower. By contrast, jurisdictions that care more about growth and dynamism will err on the side of setting the resilience standard too low.

BIS WP790, Page 5

He acknowledges there are no easy answers but asking the right questions is obviously a good place to start.

A “Money-Credit Constitution”

In addition to helping frame the broader parameters of the problem for public debate, central bankers also need to decide what their roles and responsibilities in the financial system should be. Enter the idea of a Money-Credit Constitution (MCC). I have to confess that this was a new bit of jargon for me and I had to do a bit of research to be sure that I knew what Tucker means by it. The concept digs down into the technical aspects of central banking but it also highlights the extent to which unelected technocrats have been delegated a great deal of power by the electorate. I interpret Tucker’s use of the term “constitution”as an allusion to the need for the terms on which this power is exercised to be defined and more broadly understood.

A Money-Credit Constitution defined:

“By that I mean rules of the game for both banking and central banking designed to ensure broad monetary stability, understood as having two components: stability in the value of central bank money in terms of goods and services, and also stability of private-banking-system deposit money in terms of central bank money.”

Chapter 1: How can central banks deliver credible commitment and be “Emergency Institutions”? by John Tucker in “Central Bank Governance and Oversight Reform, edited by Cochrane and Taylor (2016)

The jargon initially obscured the idea (for me at least) but some practical examples helped clarify what he was getting at. Tucker defines the 19th and early 20th century MCC as comprising; the Gold Standard, reserve requirements for private banks and the Lender of Last Resort (LOLR) function provided by the central bank. The rules of the game (or MCC) have of course evolved over time. In the two to three decades preceding the 2008 GFC, the rules of the game incorporated central bank independence, inflation targeting and a belief in market efficiency/discipline. Key elements of that consensus were found to be woefully inadequate and we are in the process of building a new set of rules.

Tucker proposes that a MCC that is fit for the purpose of achieving an efficient and resilient financial system should have five key components:

– a target for inflation (or some other nominal magnitude);

– a requirement for banking intermediaries to hold reserves (or assets readily exchanged for reserves) that increases with a firm’s leverage and/or the degree of liquidity mismatch between its assets and liabilities;

– a liquidity-reinsurance regime for fundamentally solvent banking intermediaries;

– a resolution regime for bankrupt banks and other financial firms; and

– constraints on how far the central bank is free to pursue its mandate and structure its balance sheet, given that a monetary authority by definition has latent fiscal capabilities.

BIS WP, Page 9

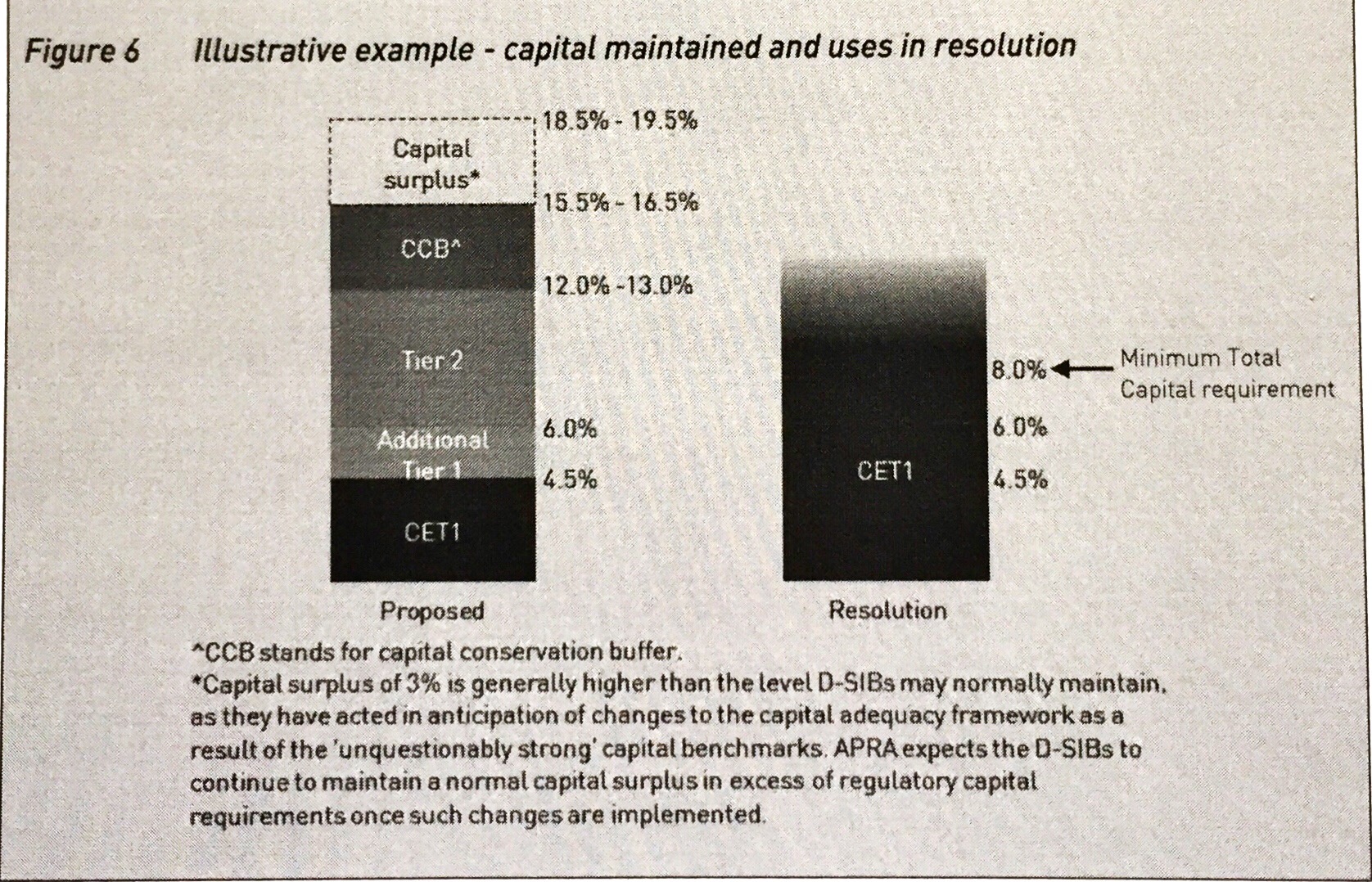

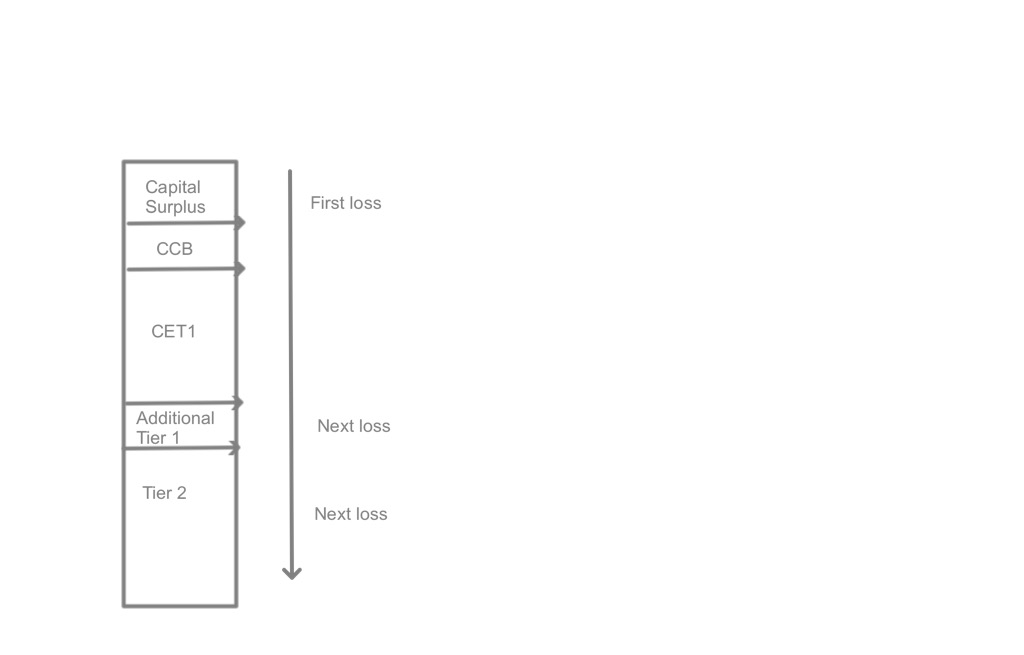

In one sense, the chosen resilience strategy for the financial system is simply determined by the combination of the capital and liquidity requirements imposed on private banks. We are using the term capital here in its broadest sense to incorporate not just common equity but also the various forms of hybrid equity and subordinated debt that can be converted into equity without disrupting the financial system.

But Tucker argues that there is a bigger question of strategy that must be addressed; that is

“whether to place the regime’s weight on regulatory requirements that impose intrinsic resilience on bank balance sheets or on credible crisis management that delivers safety ex post. It is a choice with very different implications for transparency.”

BIS WP 790; Page 11

Two alternative strategies for achieving a target state of financial system resilience

Strategy 1: Crisis prevention (or mitigation at least)

The first strategy is essentially an extension of what we have already been doing for some time; a combination of capital and liquidity requirements that limits the risk of financial crisis to some pre-determined acceptable level.

“… authorities set a regulatory minimum they think will be adequate in most circumstances and supervise intermediaries to check whether they are exposed to outsized risks.

BIS WP 790, Page 11

Capital and liquidity requirements were increased under Basel III but there was nothing fundamentally new in this part of the Basel III package. Tucker argues that the standard of resilience adopted should be explicit rather than implicit but he still doubts that this strategy is robust. His primary concern seems to be the risk that the standard of resilience is gradually diluted by a series of small concessions that only the technocrats understand.

“How did we know that firms are really satisfying the standard: is it enough that they say so? And how do we know that the authorities themselves have not quietly diluted or abandoned the standard?”

BIS WP 790; Page 11

Tucker has ideas for how this risk of regulatory capture might be controlled:

each year central bank staff (not policymakers) should publish a complete statement of all relaxations and tightenings of regulatory and supervisory policy (including in stress testing models, rules, idiosyncratic requirements, and so on)

the integrity of such assessments should be subject to external audit of some kind (possibly by the central auditor for the state).

BIS WP 790, Page 12

… but this is still a second best approach in his assessment; he argues that we can do better and the idea of making certain assets “informationally insensitive” is the organising principle driving the alternative strategies he lays out.

Strategy 2: Making assets informationally insensitive via crisis-management regimes

Tucker identifies two approaches to crisis management both based around the objective of ensuring that the value of certain agreed liabilities, issued by a defined and pre-determined set of financial intermediaries, is insensitive to information about the financial condition of these intermediaries:

Strategy 2a: Integrate LOLR with liquidity policy.

Central bankers, as the suppliers of emergency liquidity assistance, could make short term liabilities informationally insensitive by requiring banks to hold reserves or eligible collateral against all runnable liabilities. Banks would be required to cover “x”% of short term liabilities with reserves and/or eligible collateral. The key policy choices then become

- The definition of which short term liabilities drive the liquidity requirement;

- The instruments that would be eligible collateral for liquidity assistance; and

- The level of haircuts set by central banks against eligible collateral

What Tucker is outlining here is a variation on a proposal that Mervyn King set out in his book “The End of Alchemy” which I covered in a previous post. These haircuts operate broadly analogously to the existing risk-weighted equity requirements. Given the focus on emergency requirements, they would be based on stress testing and incorporate systemic risk surcharges.

Tucker is not however completely convinced by this approach:

“… a policy of completely covering short-term labilities with central bank-eligible assets would leave uninsured short-term liabilities safe only when a bank was sound. They would not be safe when a bank was fundamentally unsound.

That is because central banks should not (and in many jurisdictions cannot legally) lend to banks that have negative net assets (since LOLR assistance would allow some short-term creditors to escape whole at the expense of equally ranked longer-term creditors). This is the MCC’s financial-stability counterpart to the “no monetary financing” precept for price stability.

Since only insured-deposit liabilities, not covered but uninsured liabilities, are then safe ex post, uninsured liability holders have incentives to run before the shutters come down, making their claims information sensitive after all.

More generally, the lower E, the more frequently banks will fail when the central bank is, perforce, on the sidelines. This would appear to take us back, then, to the regulation and supervision of capital adequacy, but in a way that helps to keep our minds on delivering safety ex post and so information insensitivity ex ante.”

BIS WP 790, Page 14

Strategy 2b: Resolution policy – Making operational liabilities informationally insensitive via structure

Tucker argues that the objective of resolution policy can be interpreted as making the operational liabilities of banks, dealers and other intermediaries “informationally insensitive”. He defines “operational liabilities” as “… those liabilities that are intrinsically bound to the provision of a service (eg large deposit balances, derivative transactions) or the receipt of a service (eg trade creditors) rather than liabilities that reflect a purely risk-based financial investment by the creditor and a source of funding/leverage for the bank or dealer”

Tucker proposes that this separation of operational liabilities from purely financial liabilities can be “… made feasible through a combination of bail-in powers for the authorities and, crucially, restructuring large and complex financial groups to have pure holding companies that issue the bonds to be bailed-in” (emphasis added).

Tucker sets out his argument for structural subordination as follows.

“…provided that the ailing operating companies (opcos) can be recapitalised through a conversion of debt issued to holdco …., the opcos never default and so do not go into a bankruptcy or resolution process. While there might be run once the cause of the distress is revealed, the central bank can lend to the recapitalised opco …

This turns on creditors and counterparties of opcos caring only about the sufficiency of the bonds issued to the holdco; they do not especially care about any subsequent resolution of the holding company. That is not achieved, however, where the bonds to be bailed in … are not structurally subordinated. In that respect, some major jurisdictions seem to have fallen short:

Many European countries have opted not to adopt structural subordination, but instead have gone for statutory subordination (eg Germany) or contractual subordination (eg France).

In consequence, a failing opco will go into resolution

This entails uncertainty for opco liability holders given the risk of legal challenge etc

Therefore, opco liabilities under those regimes will not be as informationally insensitive as would have been possible.

BIS WP 790, Page 15

While structural subordination is Tucker’s preferred approach, his main point is that the solution adopted should render operational liabilities informationally insensitive:

“….the choice between structural, statutory and contractual subordination should be seen not narrowly in terms of simply being able to write down and/or convert deeply subordinated debt into equity, but rather more broadly in terms of rendering the liabilities of operating intermediaries informationally insensitive. The information that investors and creditors need is not the minutiae of the banking business but the corporate finance structure that enables resolution without opcos formally defaulting or going into a resolution process themselves

BIS WP 790 , Pages 15-16

If jurisdictions choose to stick with contractual or statutory subordination, Tucker proposes that they need to pay close attention to the creditor hierarchy, especially where the resolution process is constrained by the requirement that no creditor should be worse off than would have been the case in bankruptcy. Any areas of ambiguity should be clarified ex ante and, if necessary, the granularity of the creditor hierarchy expanded to ensure that the treatment of creditors in resolution is what is fair, expected and intended.

Tucker sums up the policy implications of this part of his paper as follows ...

“The policy conclusion of this part of the discussion, then, is that in order to deliver information insensitivity for some of the liabilities of operating banks and dealers, policymakers should:

a) move towards requiring that all short-term liabilities be covered by assets eligible at the central bank; and, given that that alone cannot banish bankruptcy,

b) be more prescriptive about corporate structures and creditor hierarchies since they matter hugely in bankruptcy and resolution.”

BIS WP 790, Page 16

Summing up …

- Tucker positions his paper as “… a plea to policymakers to work with researchers to re-examine whether enough has been done to make the financial system resilient“.

- His position is that “… the financial system is much more resilient than before the crisis but … less resilient than claimed by policymakers”

- Tucker’s assessment “… is partly due to shifts in the macroeconomic environment” which reduce the capacity of monetary and fiscal policy stimulus but also an in principle view that “maintaining a resilient system cannot sanely rely on crushing the probability of distress via prophylactic regulation and supervision: a strategy that confronts the Gods in its technocratic arrogance“.

- Tucker argues that the desired degree of resilience is more likely to be found in a combination of “… low barriers to entry, credible resolution regimes and crisis management tools …[that] … ensure the system can keep going through distress”.

- Tucker also advocates putting the central insights of some theoretical work on “informational insensitivity” to practical use in the following way:

- move towards requiring all banking-type intermediaries to cover all short-term liabilities with assets eligible for discount at the Window

- insist upon structural subordination of bailinable bonds so that the liabilities of operating subsidiaries are more nearly informationally insensitive

- be more prescriptive about the permitted creditor hierarchy of operating intermediaries

- establish frameworks for overseeing and regulating collateralised money market, with more active use made of setting minimum haircut requirements to ensure that widely used money market instruments are safe in nearly all circumstancesarticulating restrictive principles for market-maker of last resort operations

- Given the massive costs (economic, social, cultural) associated with financial crises, err on the side of maintaining resilience

- To the extent that financial resilience continues to rely on the regulation and supervision of capital adequacy, ensure transparency regarding the target level of resilience and the extent to which discretionary policy actions impact that level of resilience

I am deeply touched if you actually read this far. The topic of crisis management and resolution capability is irredeemably technical but also important to get right.

Tony