The economic rational for higher bank capital requirements that have been implemented under Basel III is built to a large extent on an analytical model developed by the BCBS that was published in a study released in 2010. The BCBS has just (June 2019) released a paper by one of its working groups which reviews the original analysis in the light of subsequent studies into the optimal capital question. The 2019 Review concludes that the higher capital requirements recommended by the original study have been supported by these subsequent studies and, if anything, the optimal level of capital may be higher than that identified in the original analysis.

Consistent with the Basel Committee’s original assessment, this paper finds that the net macroeconomic benefits of capital requirements are positive over a wide range of capital levels. Under certain assumptions, the literature finds that the net benefits of higher capital requirements may have been understated in the original Committee assessment. Put differently, the range of estimates for the theoretically-optimal level of capital requirements … is likely either similar or higher than was originally estimated by the Basel Committee.

The costs and benefits of bank capital – a review of the literature; BCBS Working Paper (June 2019)

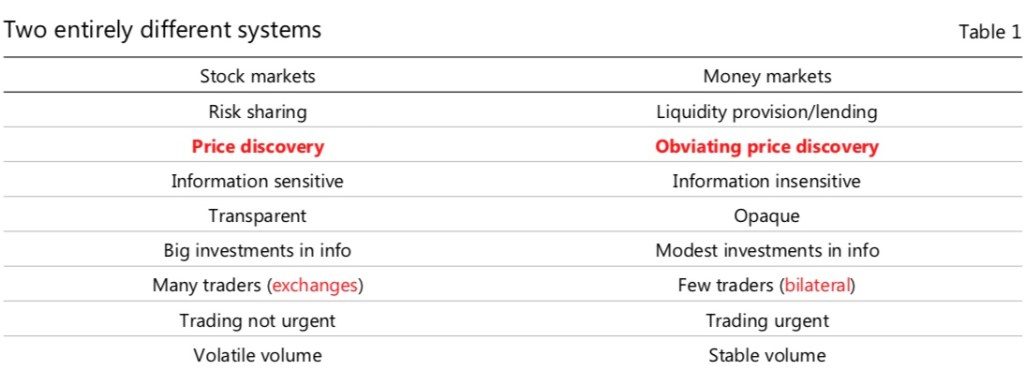

For anyone who is interested in really understanding this question as opposed to simply looking for evidence to support a preconceived bias or vested interest, it is worth digging a bit deeper into what the paper says. A good place to start is Table 1 from the 2019 Review (copied below) which compares the assumptions, estimates and conclusions of these studies:

Pay attention to the fine print

All of these studies share a common analytical model which measures Net benefits as a function of:

Reduced Crisis Probability x Crisis Cost – Output Drag (loan spreads).

So the extent of any net benefit depends on the extent to which:

- More capital actually reduces the probability of a crisis and/or its economic impact,

- The economic impact of a financial crisis is a permanent or temporary adjustment to the long term growth trajectory of the economy – a permanent effect supports the case for higher capital, and

- The cost of bank debt declines in response to higher capital – in technical terms the extent of the Modigliani Miller (MM) offset, with a larger offset supporting the case for higher capital.

The authors of the 2019 Review also acknowledge that interpretation of the results of the studies is complicated by the fact that different studies use different measures of capital adequacy. Some of the studies provide optimal capital estimates in risk weighted ratios, others in leverage ratios. The authors of the 2019 Review have attempted to convert the leverage ratios to a risk weighted equivalent but that process will inevitably be an imperfect science. The definition of capital also differs (TCE, Tier 1 & CET1).

The authors acknowledge that full standardisation of capital ratios is very complex and lies beyond the scope of their review and nominate this as an area where further research would be beneficial. In the interim (and at the risk of stating the obvious) the results and conclusions of this 2019 Review and the individual studies it references should be used with care. The studies dating from 2017, for example, seem to support a higher value for the optimal capital range compared to the 2010 benchmark. The problem is that it is not clear how these higher nominal ratio results should be interpreted in the light of increases in capital deductions and average risk weights such as we have seen play out in Australia.

The remainder of this post will attempt to dig a bit deeper into some of the components of the net benefit model employed in these types of studies.

Stability benefits – reduced probability of a crisis

The original 2010 BCBS study concluded that increasing Tangible Common Equity from 7% to 10% would reduce the probability of a financial crisis by 1.6 percentage points.

The general principle is that a financial crisis is a special class of economic downturn in which the severity and duration is exacerbated by a collapse in confidence in the banking system due to widespread doubts about the solvency of one or more banks which results in a contraction in the supply of credit.

It follows that higher capital reduces the odds that any given level of loss can threaten the actual or perceived solvency of the banking system. So far so good, but I think it is helpful at this point to distinguish the core losses that flow from the underlying problem (e.g. poor credit origination or risk management) versus the added losses that arise when credit supply freezes in response to concerns about the solvency or liquidity of the banking system.

Higher capital (and liquidity) requirements can help to mitigate the risk of those second round losses but they do not in any way reduce the economic costs of the initial poor lending or risk management. The studies however seem to use the total losses experienced in historical financial crises to calculate the net benefit rather than specific output losses that can be attributed to credit shortages and any related drop in employment and/or the confidence of business and consumers. That poses the risk that the studies may be over estimating the potential benefits of higher capital.

This is not saying that higher capital requirements are a waste of time but the modelling of optimal capital requirements must still understand the limitations of what capital can and cannot change. There is, for example, evidence that macro prudential policy tools may be more effective tools for managing the risk of systemic failures of credit risk management as opposed to relying on the market discipline of equity investors being required to commit more “skin in the game“.

Cost of a banking crisis

The 2019 Review notes that

“recent refinements associated with identifying crises is promising. Such refinements have the potential to affect estimates of the short- and long-run costs of crises as well as our understanding of how pre-crisis financial conditions affect these costs. Moreover, the identification of crises is important for estimating the relationship between banking system capitalisation and the probability of a crisis, which is likely to depend on real drivers (eg changes in employment) as well as financial drivers (eg bank capital).

We considered above the possibility that there may be fundamental limitations on the extent to which capital alone can impact the probability, severity and duration of a financial crisis. The 2019 Review also acknowledges that there is an ongoing debate, far from settled, regarding the extent to which a financial crisis has a permanent or temporary effect on the long run growth trajectory of an economy. This seemingly technical point has a very significant impact on the point at which these studies conclude that the costs of higher capital outweigh the benefits.

The high range estimates of the optimal capital requirement in these studies typically assume that the impacts are permanent. This is big topic in itself but Michael Redell’s blog did a post that goes into this question in some detail and is worth reading.

Banking funding costs – the MM offset

The original BCBS study assumed zero offset (i.e. no decline in lending rates in response to deleveraging). This assumption increase the modelled impact of higher capital and, all other things equal, reduces the optimal capital level. The later studies noted in the BCBS 2019 Review have tended to assume higher levels of MM offset and the 2019 Review concludes that the “… assumption of a zero offset likely overstated the costs of higher capital nonbank loan rates”. For the time being the 2019 Review proposes that “a fair reading of the literature would suggest the middle of the 0 and 100% extremes” and calls for more research to “… help ground the Modigliani-Miller offset used in estimating optimal bank capital ratios”.

Employing a higher MM offset supports a higher optimal capital ratio but I am not convinced that even the 50% “split the difference” compromise is the right call. I am not disputing the general principle that risk and leverage are related. My concern is that the application of this general principle does not recognise the way in which some distinguishing features of bank balance sheets impact bank financing costs and the risk reward equations faced by different groups of bank stakeholders. I have done a few posts previously (here and here) that explore this question in more depth.

Bottom line – the BCBS itself is well aware of most of the issues with optimal capital studies discussed in this post – so be wary of anyone making definitive statements about what these studies tell us.

The above conclusion is however subject to a number of important considerations. First, estimates of optimal capital are sensitive to a number of assumptions and design choices. For example, the literature differs in judgments made about the permanence of crisis effects as well as assumptions about the efficacy of post crisis reforms – such as liquidity regulations and bank resolution regimes – in reducing the probability and costs of future banking crisis. In some cases, these judgements can offset the upward tendency in the range of optimal capital.

Second, differences in (net) benefit estimates can reflect different conditioning assumptions such as starting levels of capital or default thresholds (the capital ratio at which firms are assumed to fail) when estimating the impact of capital in reducing crisis probabilities.2

Finally, the estimates are based on capital ratios that are measured in different units. For example, some studies provide optimal capital estimates in risk-weighted ratios, others in leverage ratios. And, across the risk-weighted ratio estimates, the definition of capital and risk-weighted assets (RWAs) can also differ (eg tangible common equity (TCE) or Tier 1 or common equity tier 1 (CET1) capital; Basel II RWAs vs Basel III measures of RWAs). A full standardisation of the different estimates across studies to allow for all of these considerations is not possible on the basis of the information available and lies beyond the scope of this paper.

This paper also suggests a set of issues which warrant further monitoring and research. This includes the link between capital and the cost and probability of crises, accounting for the effects of liquidity regulations, resolution regimes and counter-cyclical capital buffers, and the impact of regulation on loan quantities.

The costs and benefits of bank capital – a review of the literature; BCBS Working Paper (June 2019)

Summing up

I would recommend this 2019 Literature Review to anyone interested in the question of how to determine the optimal capital requirements for banks. The topic is complex and important and also one where I am acutely aware that I may be missing something. I repeat the warning above about anyone (including me) making definitive statements based on these types of studies.

That said, the Review does appear to offer support for the steps the BCBS has taken thus far to increase capital and liquidity requirements. There are also elements of the paper that might be used to support the argument that bank capital requirements should be higher again. This is the area where I think the fine print offers a more nuanced perspective.

Tony