The somewhat arcane topic of mortgage risk weights is back in the news. It gets popular attention to the extent they impact the ability of small banks subject to standardised risk weights to compete with bigger banks which are endorsed to use the more risk sensitive version based on the Internal Ratings Based (IRB) approach. APRA released a Discussion Paper (DP) in February 2018 titled “Revisions to the capital framework for authorised deposit-taking institutions”. There are reports that APRA is close to finalising these revisions and that this will address the competitive disadvantage that small banks suffer under the current regulation.

This sounds like a pretty simple good news story – a victory for borrowers and the smaller banks – and my response to the discussion paper when it was released was that there was a lot to like in what APRA proposed to do. I suspect however that it is a bit more complicated than the story you read in the press.

The difference in capital requirements is overstated

Let’s start with the claimed extent of the competitive disadvantage under current rules. The ACCC’s Final Report on its “Residential Mortgage Price Inquiry” described the challenge with APRA’s current regulatory capital requirements as follows:

“For otherwise identical ADIs, the advantage of a 25% average risk weight (APRA’s minimum for IRB banks) compared to the 39% average risk weight of standardised ADIs is a reduction of approximately 0.14 percentage points in the cost of funding the loan portfolio. This difference translates into an annual funding cost advantage of almost $750 on a residential mortgage of $500 000, or about $15 000 over the 30 year life of a residential mortgage (assuming an average interest rate of 7% over that period).”

You could be forgiven for concluding that this differential (small banks apparently required to hold 56% more capital for the same risk) is outrageous and unfair.

Just comparing risk weights is less than half the story

I am very much in favour of a level playing field and, as stated above, I am mostly in favour of the changes to mortgage risk weights APRA outlined in its discussion paper but I also like fact based debates.

While the risk weights for big banks are certainly lower on average than those required of small banks, the difference in capital requirements is not as large as the comparison of risk weights suggests. To understand why the simple comparison of risk weights is misleading, it will be helpful to start with a quick primer on bank capital requirements.

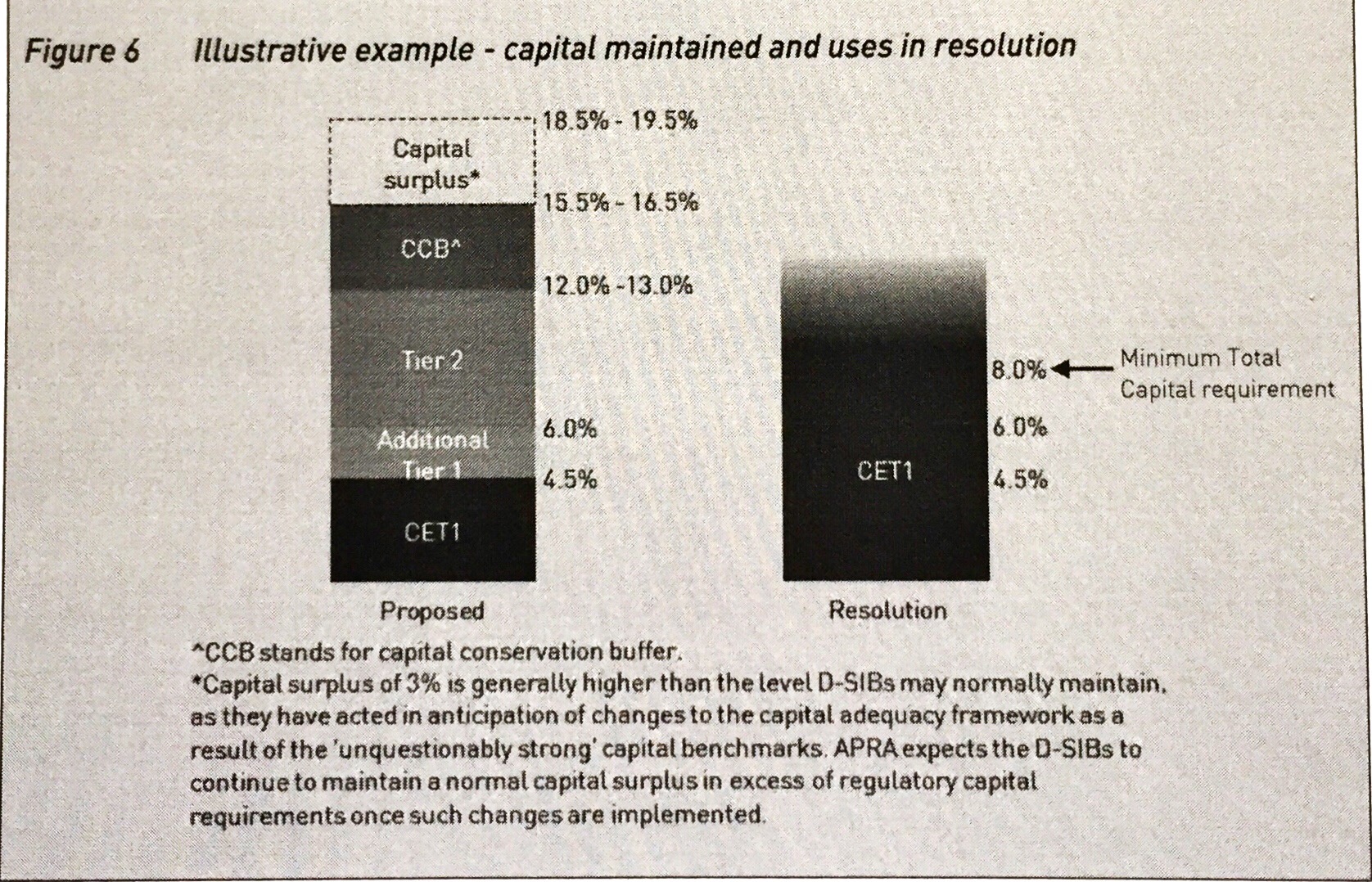

The topic can be hugely complex but, reduced to its essence, there are three elements that drive the amount of capital a bank holds:

- The risk weights applied to its assets

- The target capital ratio applied to those risk weighted assets

- Any capital deductions required when calculating the capital ratio

I have looked at this question a couple of times (most recently here) and identified a number of problems with the story that the higher risk weights applied to residential mortgages originated by small bank places them at a severe competitive disadvantage:

Target capital ratios – The target capital adequacy ratios applied to their higher standardised risk weighted assets are in some cases lower than the IRB banks and higher in others (i.e. risk weights alone do not determine how much capital a bank is required to hold).

Portfolio risk – The risk of a mortgage depends on the portfolio not the individual loan. The statement that a loan is the same risk irrespective of whether it is written by a big bank or small bank sounds intuitively logical but is not correct. The risk of a loan can only be understood when it is considered as part of the portfolio the bank holds. All other things being equal, small banks will typically be less diversified and hence riskier than a big bank.

Capital deductions – You also have to include capital deductions and the big banks are required to hold capital for a capital deduction linked to the difference between their loan loss provisions and a regulatory capital value called “Regulatory Expected Loss”. The exact amount varies from bank to bank but I believe it increases the effective capital requirement by 10-12% (i.e. an effective RW closer to 28% for the IRB banks).

IRRBB capital requirement – IRB banks must hold capital for Interest Rate Risk in the Banking Book (IRRBB) while the small standardised banks do not face an explicit requirement for this risk. I don’t have sufficient data to assess how significant this is, but intuitively I would expect that the capital that the major banks are required to hold for IRRBB will further narrow the effective difference between the risk weights applied to residential mortgages.

How much does reducing the risk weight differential impact competition in the residential mortgage market?

None of the above is meant to suggest that the small banks operating under the standardised approach don’t have a case for getting a lower risk weight for their higher quality lower risk loans. If the news reports are right then it seems that this is being addressed and that the gap will be narrower. However, it is important to remember that:

- The capital requirement that the IRB banks are required to maintain is materially higher than a simplistic application of the 25% average risk weight (i.e. the IRB bank advantage is not as large as it is claimed to be).

- The standardised risk weight does not seem to be the binding constraint so reducing it may not help the small banks much if the market looks through the change in regulatory risk measurement and concludes that nothing has changed in substance.

One way to change the portfolio quality status quo is for small banks to increase their share of low LVR loans with a 20% RW. Residential mortgages do not, for the most part, get originated at LVR of sub 50% but there is an opportunity for small banks to try to refinance seasoned loans where the dynamic LVR has declined. This brings us to the argument that IRB banks are taking the “cream” of the high quality low risk lending opportunities.

The “cream skimming” argument

A report commissioned by COBA argued that:

“While average risk weights for the major banks initially rose following the imposition of average risk weight on IRB banks by APRA, two of the major banks have since dramatically reduced their risk weights on residential mortgages with the lowest risk of default. The average risk weights on such loans is now currently on average less than 6 per cent across the major banks.”

“Despite the imposition of an average risk weight on residential home loans, it appears some of the major banks have decided to engage in cream skimming by targeting home loans with the lowest risk of default. Cream skimming occurs when the competitive pressure focuses on the high-demand customers (the cream) and not on low- demand ones (the skimmed milk) (Laffont & Tirole, 1990, p. 1042). Cream skimming has adverse consequences as it skews the level of risk in house lending away from the major banks and towards other ADIs who have to deal with an adversely selected and far riskier group of home loan applicants.”

“Reconciling Prudential Regulation with Competition” prepared by Pegasus Economics May 2019 (page 43)

It is entirely possible that I am missing something here but, from a pure capital requirement perspective, it is not clear that IRB banks have a material advantage in writing these low risk loans relative to the small bank competition. The overall IRB portfolio must still meet the 25% risk weight floor so any loans with 6% risk weights must be offset by risk weights (and hence riskier loans) that are materially higher than the 25% average requirement. I suspect that the focus on higher quality low risk borrowers by the IRB banks was more a response to the constraints on capacity to lend than something that was driven by the low risk weights themselves.

Under the proposed revised requirements, small banks in fact will probably have the advantage in writing sub 50% LVR loans given that they can do this at a 20% risk weight without the 25% floor on their average risk weights and without the additional capital requirements the IRB banks face.

I recognise there are not many loans originated at this LVR band but there is an opportunity in refinancing seasoned loans where the combined impact of principal reduction and increased property value reduces the LVR. In practice the capacity of small banks to do this profitably will be constrained by their relative expense and funding cost disadvantage. That looks to me to be a bigger issue impacting the ability of small banks to compete but that lies outside the domain of regulatory capital requirements.

Maybe this potential arbitrage does not matter in practice but APRA could quite reasonably impose a similar minimum average RW on Standardised Banks if the level playing field argument works both ways. This should be at least 25% but arguably higher once you factor in the fact that the small banks do not face the other capital requirements that IRB banks do. Even if APRA did not do this, I would expect the market to start looking more closely at the target CET1 for any small bank that accumulated a material share of these lower risk weight loans.

Implications

Nothing in this post is meant to suggest that increasing the risk sensitivity of the standardised risk weights is a bad idea. It seems doubtful however that this change alone will see small banks aggressively under cutting large bank competition. It is possible that small bank shareholders may benefit from improved returns on equity but even that depends on the extent to which the wholesale markets do not simply look through the change and require smaller banks to maintain the status quo capital commitment to residential mortgage lending.

What am I missing …