Depositors tend to be a protected species

It is generally agreed that bank deposits have a privileged position in the financial system. There are exceptions to the rule such as NZ which, not only eschews deposit insurance, but also the practice of granting deposits a preferred (or super senior) claim on the assets of the bank. NZ also has a unique approach to bank resolution which clearly includes imposing losses on bank deposits as part of the recapitalisation process. Deposit insurance is under review in NZ but it is less clear if that review contemplates revisiting the question of deposit preference.

The more common practice is for deposits to rank at, or near, the top of the queue in their claim on the assets of the issuing bank. This preferred claim is often supported by some form of limited deposit insurance (increasingly so post the Global Financial Crisis of 2008). An assessment of the full benefit has to consider the cost of providing the payment infrastructure that bank depositors require but the issuing bank benefits from the capacity to raise funds at relatively low interest rates. The capacity to raise funding in the form of deposits also tends to mean that the issuing banks will be heavily regulated which adds another layer of cost.

The question is whether depositors should be protected

I am aware of two main arguments for protecting depositors:

- One is to protect the savings of financially unsophisticated individuals and small businesses.

- The other major benefit relates to the short-term, on-demand, nature of deposits that makes them convenient for settling transactions but can also lead to a ‘bank run’.

The fact is that retail depositors are simply not well equipped to evaluate the solvency and liquidity of a bank. Given that even the professionals can fail to detect problems in banks, it is not clear why people who will tend to lie at the unsophisticated end of the spectrum should be expected to do any better. However, the unsophisticated investor argument by itself is probably not sufficient. We allow these individuals to invest in the shares of banks and other risky investments so what is special about deposits.

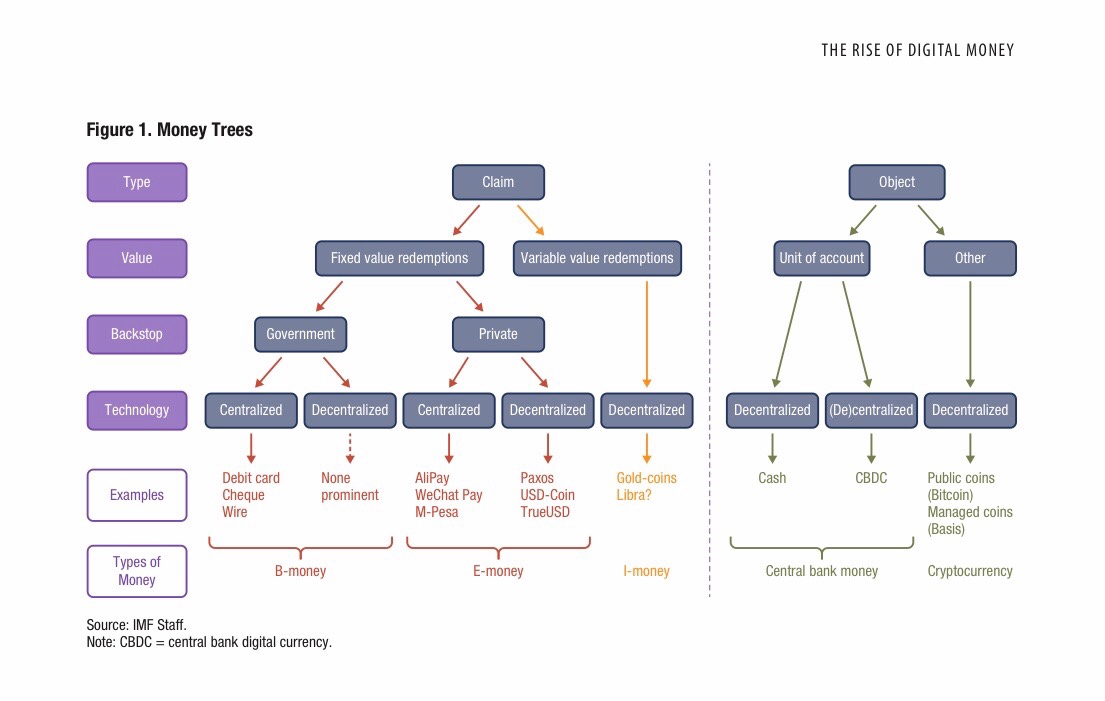

The more fundamental issue is that, by virtue of the way in which they function as a form of money, bank deposits should not be analysed as “investments”. To function as money the par value of bank deposits must be unquestioned and effectively a matter of faith or trust. Deposit insurance and deposit preference are the tools we use to underwrite the safety and liquidity of bank deposits and this is essential if bank deposits are to function as money. We know the economy needs money to facilitate economic activity so if bank deposits don’t perform this function then you need something else that does. Whatever the alternative form of money decided on, you are still left with the core issue of how to make it safe and liquid.

Quote

“The capacity of a financial instrument like a bank deposit to be accepted and used as money depends on the ability of uninformed agents to trade it without fear of loss; i.e. the extent to which the value of the instrument is insulated from any adverse information about the counterparty”

Gary Gorton and George Pennacchi “Financial Intermediaries and Liquidity Creation”

I recognise that fintech solutions are increasingly offering alternative payment mechanisms that offer some of the functions of money but to date these still ultimately rely on a bank with a settlement account at the central bank to function. This post on Alphaville is worth reading if you are interested in this area of financial innovation. The short version is that fintechs have not been able to create new money in the way banks do but this might be changing.

But what about moral hazard?

There is an argument that depositors should not be a protected class because insulation from risk creates moral hazard.

While government deposit insurance has proven very successful in protecting banks from runs, it does so at a cost because it leads to moral hazard (Santos, 2000, p. 8). By offering a guarantee that depositors are not subject to loss, the provider of deposit insurance bears the risk that they would otherwise have borne.

According to Dr Sam Wylie (2009, p. 7) from the Melbourne Business School:

“The Government eliminates the adverse selection problem of depositors by insuring them against default by the bank. In doing so the Government creates a moral hazard problem for itself. The deposit insurance gives banks an incentive to make higher risk loans that have commensurately higher interest payments. Why?, because they are then betting with taxpayer’s money. If the riskier loans are repaid the owners of the bank get the benefit. If not, and the bank’s assets cannot cover liabilities, then the Government must make up the shortfall”

Reconciling Prudential Regulation with Competition, Pegasus Economics, May 2019 (p17)

A financial system that creates moral hazard is clearly undesirable but, for the reasons set out above, it is less clear to me that bank depositors are the right set of stakeholders to take on the responsibility of imposing market discipline on banks. There is a very real problem here but requiring depositors to take on this task is not the answer.

The paper by Gorton and Pennacchi that I referred to above notes that there is a variety of ways to make bank deposits liquid (i.e. insensitive to adverse information about the bank) but they argue for solutions where depositors have a sufficiently deep and senior claim on the assets of the bank that any volatility in their value is of no concern. This of course is what deposit insurance and giving deposits a preferred claim in the bank loss hierarchy does. Combining deposit insurance with a preferred claim on a bank’s assets also means that the government can underwrite deposit insurance with very little risk of loss.

It is also important I think to recognise that deposit preference moves the risk to other parts of the balance sheet that are arguably better suited to the task of exercising market discipline. The quote above from Pegasus Economics focussed on deposit insurance and I think has a fair point if the effect is simply to move risk from depositors to the government. That is part of the reason why I think that deposit preference, combined with how the deposit insurance is funded, are also key elements of the answer.

Designing a banking system that addresses the role of bank deposits as the primary form of money without the moral hazard problem

I have argued that the discussion of moral hazard is much more productive when the risk of failure is directed at stakeholders who have the expertise to monitor bank balance sheets, the capacity to absorb the risk and who are compensated for undertaking this responsibility. If depositors are not well suited to the market discipline task then who should bear the responsibility?

- Senior unsecured debt

- Non preferred senior debt (Tier 3 capital?)

- Subordinated debt (i.e. Tier 2 capital)

- Additional Tier 1 (AT1)

- Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1)

There is a tension between liquidity and risk. Any security that is risky may be liquid during normal market conditions but this “liquidity” cannot be relied on under adverse conditions. Senior debt can in principle be a risky asset but most big banks will also aim to be able to issue senior debt on the best terms they can achieve to maximise liquidity. In practice, this means that big banks will probably aim for a Long Term Senior Debt Rating that is safely above the “investment grade” threshold. Investment grade ratings offer not just the capacity top issue at relatively low credit spreads but also, and possibly more importantly, access to a deeper and more reliable pool of funding.

Cheaper funding is nice to have but reliable access to funding is a life and death issue for banks when they have to continually roll over maturing debt to keep the wheels of their business turning. This is also the space where banks can access the pools of really long term funding that are essential to meet the liquidity and long term funding requirements that have been introduced under Basel III.

The best source of market discipline probably lies in the space between senior debt and common equity

I imagine that not every one will agree with me on this but I do not see common equity as a great source of market discipline on banks. Common equity is clearly a risky asset but the fact that shareholders benefit from taking risk is also a reason why they are inclined to give greater weight to the upside than to the downside when considering risk reward choices. As a consequence, I am not a fan of the “big equity” approach to bank capital requirements.

In my view, the best place to look for market discipline and the control of moral hazard in banking lies in securities that fill the gap between senior unsecured debt and common equity; i.e. non-preferred senior debt, subordinated debt and Additional Tier 1. I also see value in having multiple layers of loss absorption as opposed to one big homogeneous layer of loss absorption. This is partly because it can be more cost effective to find different groups of investors with different risk appetites. Possibly more important is that multiple layers offer both the banks and supervisors more flexibility in the size and impact of the way these instruments are used to recapitalise the bank.

Summing up …

I have held off putting this post up because I wanted the time to think through the issues and ensure (to the best of my ability) that I was not missing something. There remains the very real possibility that I am still missing something. That said, I do believe that understanding the role that bank deposits play as the primary form of money is fundamental to any complete discussion of the questions of deposit insurance, deposit preference and moral hazard in banking.

Tony